Mai Musié

Please tell us about your work in classics and/or classical reception studies (scholarship, teaching, artistic work, public engagement, etc.).

I am the Public Engagement Manager for the Bodleian Libraries. Essentially, my role is facilitating the relationship between the Bodleian Libraries and the public. This involves creating free public events at the Weston Library, the newly refurbished wing of the Bodleian, for leaners of all ages. Public engagement is at the heart of the Bodleian Libraries mission, bringing researchers and the public together: we have designed activities based on our collections to be delivered through exhibitions and displays, talks, and printing workshops, which helps us to reach a wider audience. Our schools programme is also centred on our exceptional special collections which we can cross-reference with the current school curriculum.

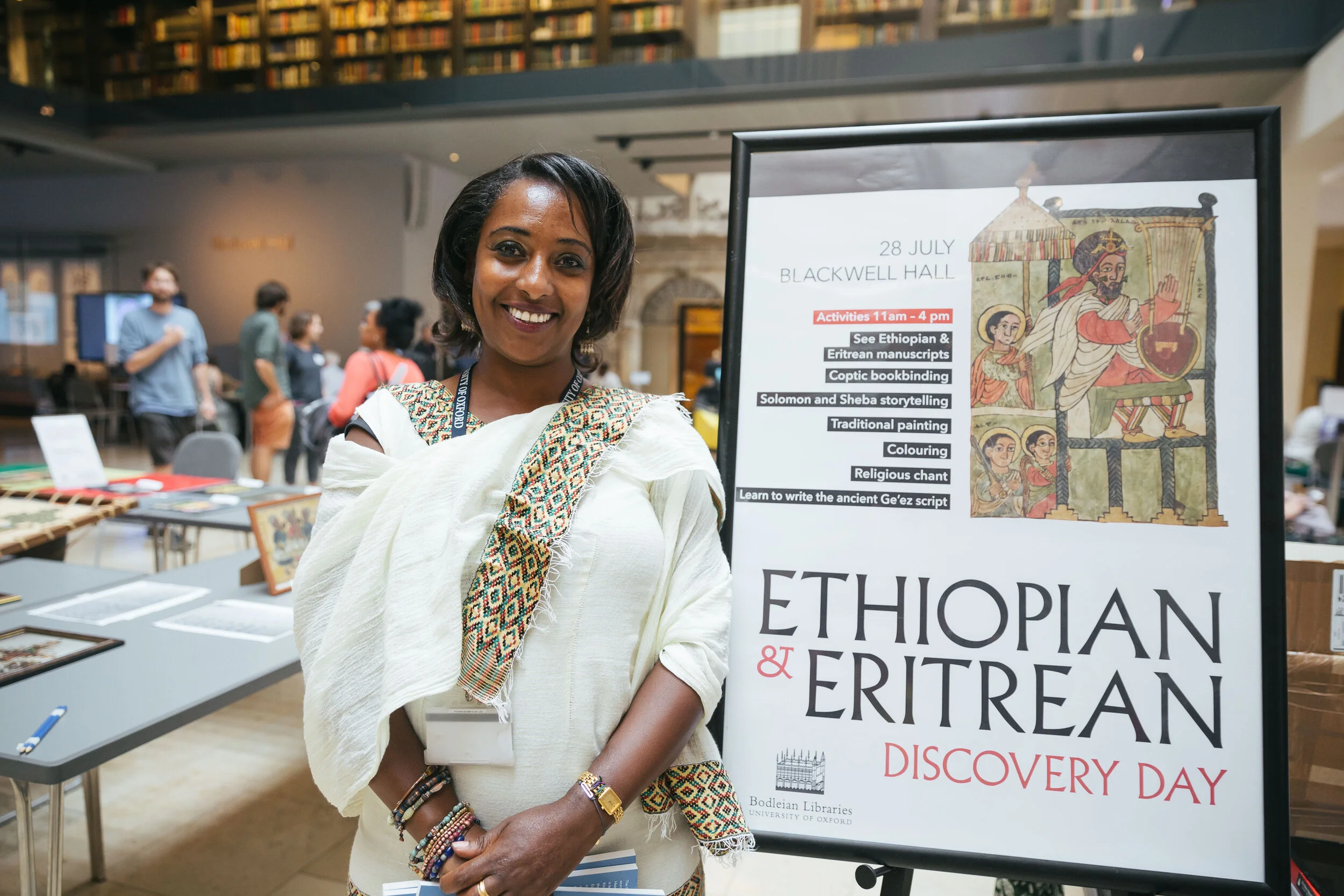

One of our main priority areas is working with specific communities on co-curation opportunities. in the past six years I had the pleasure to be involved in a co-curation project with Classics and Medieval colleagues and the diaspora communities of Ethiopia and Eritrea on ancient Ge’ez manuscripts. This project became an ideal model for knowledge exchange, defined by the ESRC (Economic and Social Research Council) as a two-way exchange between researchers and research users, to share ideas, research evidence, experiences and skills. It refers to any process through which academic ideas and insights are shared, and external perspectives and experiences brought in to academia. Researchers were able to learn from community members, leaders, and priests about the content of these manuscripts and their cultural importance for the Ethiopian and Eritrean people. The community not only became aware of the existence of these manuscripts in the Bodleian Libraries, but they also drew a sense of pride knowing that these manuscripts had a significant impact on late antiquity and medieval studies.

What were your first encounters with the field of Classics?

My path to Classics is a rather unconventional one. In 1989 I arrived in Britain as an eight-year-old refugee from Eritrea via Sudan. When I arrived on the shores of the ‘green and pleasant land’ I spoke two Semitic languages – Tigrinya and Arabic but no English. Each day after primary school I would visit the local library – South Lambeth Tate Library. It became my haven, not only were the English texts instrumental in acquiring this new and strange language but it opened the doors to literary texts from around the world.

I remember reading Little Women, The Secret Garden, entering the world of Narnia, and becoming so absorbed that I often lost myself into those imaginary worlds. I was particularly fascinated by creation myths from across the globe; epic journeys of mythical heroes, battles with monsters and gods, and the eternal search for the meaning of life. These themes and narratives intrigued me, and I often wrote myself into these stories as a way of dealing with my own chaotic and turbulent existence. The journey of self-discovery of Gilgamesh, the (mis)adventures of Loki, the death and rebirth of Osiris, the tragic tale of Orpheus and Eurydice, the traumatic impact of war as experienced through the Greek heroes such as Ajax and Achilles.

All these narrative threads woven into a fictional tapestry had a profound effect on my learning experiences. And I wanted more. Little did I know that these leisurely interests could become academic interests until I was pursuing my A Level education at St Francis Xavier Sixth Form College, South London.

Tell us about your areas of research.

Heliodorus’ work was my first immersion into the world of the ancient novel. I was particularly attracted to the tale because of my own Ethiopian-Eritrean heritage. Like the protagonists of the ancient novel my forced wanderings took me to many countries and places between East and West. My identity was constantly shifting and being reconstructed in response to people and places I encountered - racially I am black, ethnically Eritrean, and culturally British. In the ancient world one can identify as Greek or Roman but be racially and ethnically different from those who inhabited mainland Greece or Rome.

The Greek novels, although varied, all have a common theme: a young, beautiful, highly educated Greek couple after falling in love face many trials and tribulations before finally being reunited at the end of each story. These trials and tribulations usually consist of separation from each other and encounters with the Other. Their adventure (instigated by kidnappings, shipwrecks, or oracles) thrusts these heroes from the centre, the known Greek world, to the periphery inhabited by crafty Egyptians, degenerate Persians, pious Ethiopians, and mystical Indians. These diverse ethnic groups and individuals are described through the eyes of Greek protagonists and narrator, against a backdrop of a long and complex Greek (and Roman) literary and historical tradition of the representation of the Other.

How did you become interested in race and identity in the Greek novels?

It was not a surprise to me or my academic tutors that I wanted to pursue a doctoral thesis exploring the representation of the Other in the ancient Greek novels. Ethnicity and fluidity of identity is at the heart of these Greek novels and the novelists themselves; Heliodorus tells us he is Syrian, Chariton from Aphrodisias, Achilles Tatius from Alexandria, and Xenophon from Ephesus (Longus being the odd one out). Like us, the Greeks and Romans struggled to understand the variety of different races and ethnicities around them. How they viewed foreign cultures was tied up with how they viewed themselves, being Greek or Roman was fluid and oscillatory and these terms were constantly redefined, reviewed and scrutinised.

I remember when I was discussing my PhD proposal with one of my work colleagues (at the time I was working for an access programme called Reaching Wider in South Wales) and I was contemplating of how to bring in postcolonial theory into the methodological framework, my colleague gifted me Edward Säid’s Orientalism. He thought I would benefit from reading it – he was right. It felt like an epiphany moment. Säid traces the European idea of the Orient to ancient Greek and Roman sources, particularly Aeschylus’ The Persians, and Euripides’ The Bacchae. These two plays, he argues, contain motifs which come to shape the idea of the Orient as the exotic ‘Other’.

Despite it being written in the late ‘70s I found a lot of the ideas that Säid was expressing extremely relevant to our times. ‘Otherness’ and the politics of ‘Othering’ continue to have a potent force today. The results of both Britain’s Membership of the European Union Referendum and the North American election in 2016 have produced subsequent policies which can be seen and interpreted as disuniting, alienating, and dehumanising marginalised groups, the effects of which are being felt on a national and international level. The disparagement of alien societies, the denigration of an external group to formulate a collective ‘superior’ identity of one’s own, is not a new phenomenon. You can see how the world of the ancient Greeks novels may resonate for contemporary audiences – issues of race and identity are not new phenomena.

Tell us about teachers and scholars who have inspired you.

My A Level English teacher set me on the path of Classics, unwittingly. He was a fantastic teacher – quiet, unassuming but nonetheless electrified the room when he lectured on the works of Shakespeare, Jane Austen, and L.P. Hartley. The text that did it for me though was the 1993 play ‘Arcadia’ written by the playwright Tom Stoppard. I was fascinated by the classical references so much so that I signed up for a Classical excursion to Greece that the college was organising the summer prior to me attending university. I abandoned the idea of studying Law at university, a more traditional vocation, and took up Classical Civilisation instead.

Another teacher who had a profound effect on my learning was my university professor, Prof. John Morgan. He taught with infectious enthusiasm and really brought the ancient world alive. John’s specialism was Greek literature and I found myself being drawn to the Greek novels written under the Imperial Age.

I am inspired by the works of Emily Greenwood, Justine McConnell, Fiona Macintosh, Katherine Harloe, Zena Kamesh, Rachel Mairs, and countless other academics who make the ancient world relevant to modern audiences. As Classicists we need to look at the ancient world through a critical eye, we need to bring different perspectives into the field, and we need to stand up for the Classics if it is being misappropriated, particularly in the current political sphere. We can challenge the misuse and abuse of Classics through our writings, our interactions with each other, and in our classrooms.

Where do you think the field of Classics needs to go next?

The future of Classics? Well I think it is important to work together as a community of academics, teachers, and volunteers to keep the subject alive. I think we need to have honest and candid discussions about the legacy of imperialism and colonisation and how our subject is caught up in it. I work in one of the most traditionally elite institutions – elite not just in terms of ranking but in terms of being exclusive. You cannot escape from Oxford’s imperial legacy. That is why I think it is important to discuss issues such as decolonising the curriculum, restitution and repatriation of objects, in a place like Oxford. Classics can only benefit from these conversations if it truly wants to be relevant and inclusive.

For several years, I have often worked with people who have felt marginalised and on the periphery of society. Refugees, Gypsy Traveller groups, Black and Asian women who have faced domestic violence and rape – these groups of people have inspired me to try and make the world a better place. For some time now I have worked in access and outreach, trying my best to make Higher Education and Classics accessible to minority groups. I am grateful that I am not alone in this objective and there are several Classicists out there who work very hard to achieve this goal such as Arlene Holmes-Henderson, Steve Hunt, and Caroline Bristow, to name a few. There are charitable bodies too like the Iris Project, the Latin Programme, Primary Latin Project, and of course Classics for All. In 2019 I was honoured to become one of the Trustees of the latter.